One question we often get asked is “How do I know when my website is accessible?”. The answer? “It depends”.

Not what you wanted to hear? That’s ok. Read on and we’ll try to explain.

What is web accessibility?

Web accessibility is the process of ensuring that your website caters to a wide range of users’ needs. It’s not always about disability, although that is the first thing most people think of.

Let’s say your user is blind or has impaired vision. They use a screen reader, which is a piece of technology that reads the content of your website to them. They can navigate through your headings, to get straight to the content they need to. They can also fill in forms and otherwise have an enjoyable experience on your site.

Unless of course, your website isn’t accessible, then it becomes a very difficult task.

Common accessibility issues

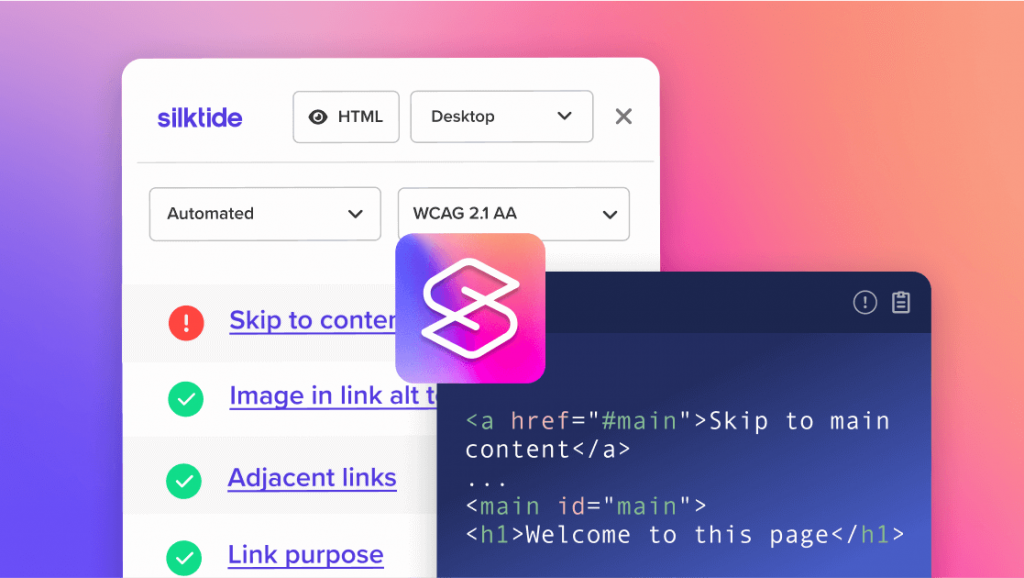

What if you missed the ‘Skip to Content’ link for screen reader users? The impact of doing so means your users might have to tab through hundreds of navigation links to read the first page heading.

What if you present useful information in images that don’t have alternative text? Or a form with no labels, so there’s no way to know where to put your name, address, or phone number?

As a sighted user, I take all these things for granted. I can scan through a webpage, see the headings and images, and get straight to the information I need.

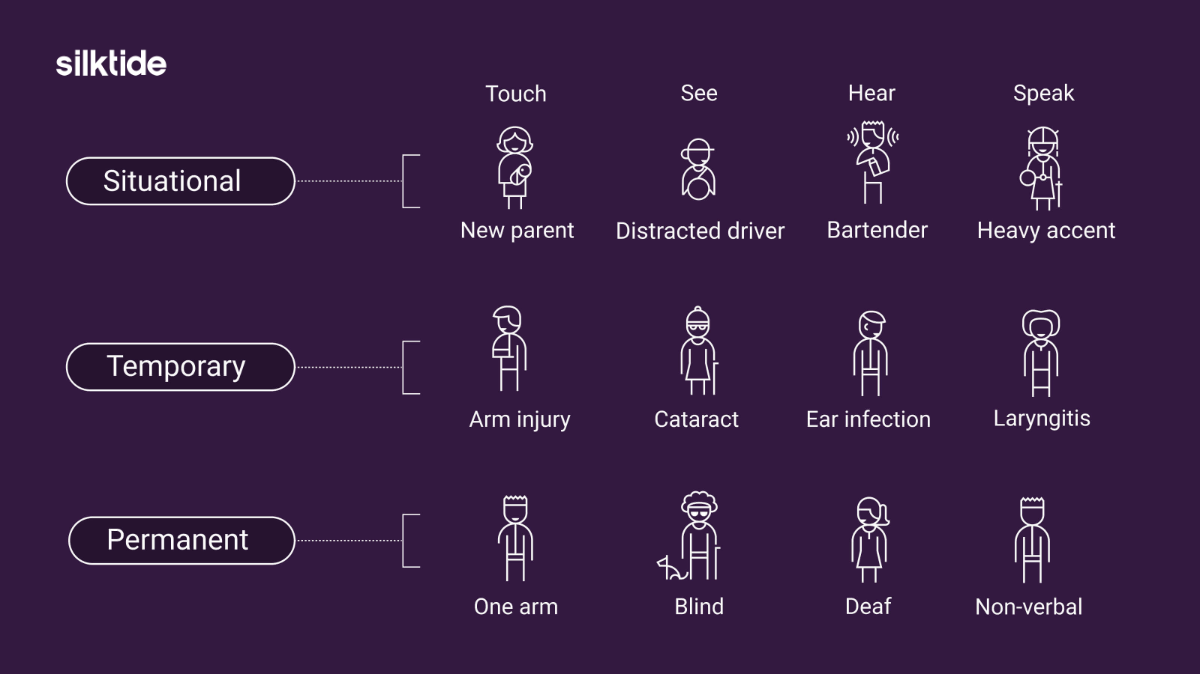

‘Situational accessibility’

Let’s consider ‘situational accessibility’. If a user has low vision then they need text contrast to be high enough that it’s readable. The same applies to a person with excellent vision who happens to be using their device in bright sunlight.

A user might not be able to hear the audio in a piece of your content because they are either deaf, have an ear infection, or are in a loud room. These three problems are all fixed with the same solution – adding subtitles and transcripts to audio and visual media.

You can understand how better accessibility benefits everybody.

The impact of not getting it right on a large percentage of your audience should not be underestimated. That said, with the right tools, knowledge, and will to change, you can provide a better online experience for everyone.

Now we’re all caught up, let’s talk about what it means to be accessible.

Accessibility is a scale, not a switch.

We’re often asked some version of the following questions, especially since we released the Silktide Index:

- Is there a score or a threshold?

- Are there some other criteria?

- Can you show me the tick box that says I am 100% accessible?

People often misunderstand, but that’s ok. It’s easy to see where this comes from. The requirements in the law pretty much state ‘you must be accessible’.

But then, no one actually gets into the finer points. What does that really mean?

The truth is, accessibility is more of a scale rather than a switch. It’s definitely not something that is on or off.

You can think of the accessibility of your site as a range, from ‘totally inaccessible’ to ‘a great experience for everyone’. Obviously, you want to be as near to ‘great’ as possible on this scale.

Ambiguity in WCAG

Silktide will grade you on this scale for all the things that are unambiguous (i.e., those that a computer can test). There are certain levels of accessibility failings that would be unambiguously interpreted as totally inaccessible.

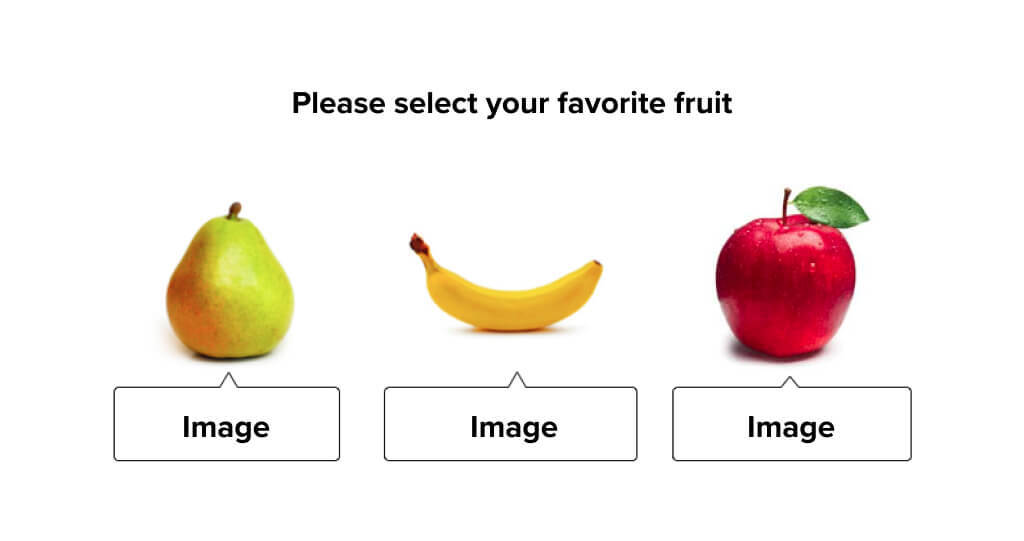

A simple example would be the image below. You’re asked to indicate your favorite fruit by selecting one of the three pictures. Without alternative text, you couldn’t know what you were clicking on. You’d be asked to select ‘image’, ‘image’, or ‘image’ by a screen reader. If you were, say, blind, that would be a classic unambiguous example, and a WCAG failure.

There are many cases however where it’s more subjective. There is a requirement in WCAG that content is easy to understand and that as many people as possible should understand your text. You should write for an audience with a reading age of around 12-13 years.

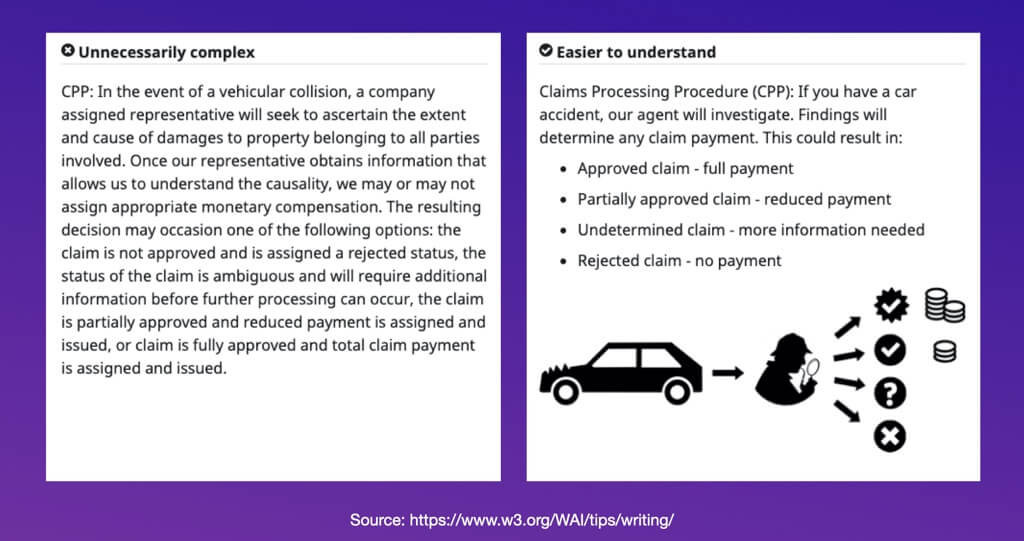

Below is an image containing two examples of the same written content. On the left, the text is provided as a single, long paragraph of around 100 words. It’s difficult to read. On the right is the same information but as a shortened bulleted list, which is much easier to digest.

It’s quite clear to a human being that what you see on the right is easier to understand than what is on the left. Indeed, a computer can determine this as well. We have all sorts of math and formula that’s designed to assess this.

But how would you actually grade that? Would you grade one as a pass and one as a failure? Technically, the material on the left is accessible in that you can at least hear it or read it. It’s just a bad experience.

A pretty strong case in this example could be made that this is failing a WCAG AAA requirement, although it isn’t as simple as yes or no. What if we take the example on the right and add one sentence that fails that criterion? Would that make the entire page a failure?

Would it make the entire website a failure? Probably not.

Manual or automated accessibility testing?

These examples come back to the differences between manual and automated testing. Think of automated testing as giving you broad coverage, while manual testing gives you in-depth, first-hand experience.

As long as you take this approach you’re engaging with the process of becoming more accessible. You understand the problems and you’re fixing them. You’re basically about as accessible as anyone is actually ever going to get.

Even the people who wrote the standards don’t meet the fullest level of that standard (being WCAG 2.1 AAA compliant across the board, and unambiguously accessible).

It’s something to strive for but generally, you should aim to pass as many of the A and AA WCAG criteria as possible.

So, how do I know when my website is accessible?

‘It depends’. We appreciate this is the kind of woolly answer that you don’t want to hear. Unfortunately, the law, and indeed the standards themselves, don’t explicitly state ‘Here is a pass, and here is a failure’.

The latest and next version of the WCAG standards is likely many years away. They are, however, aware of the problem and they are investigating ways of making it unambiguous.

A straight pass/fail is being considered. More likely is a certifiable, measurable grading system. For the moment though, there isn’t such a thing.

Some help with manual testing

If you’re looking at manual testing but you haven’t got a large budget, you can take advantage of some free tools like our accessibility toolbar for Chrome.

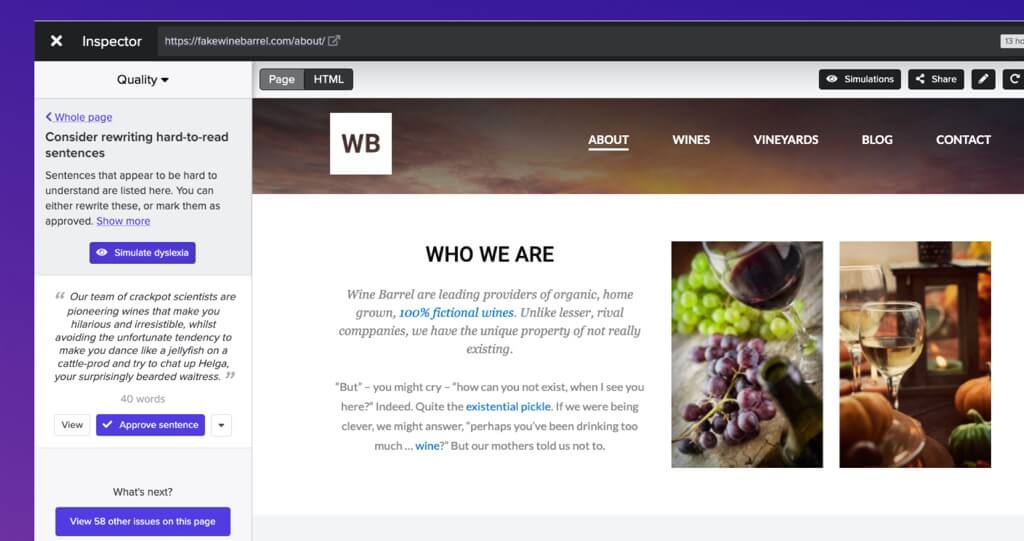

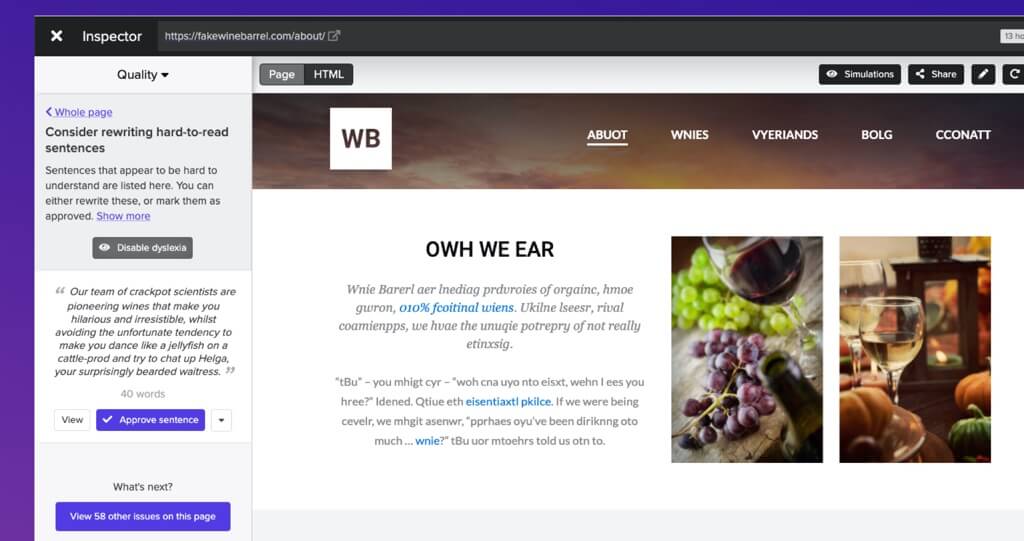

This technology is also embedded in our Inspector. Click a button and see a simulation of how that accessibility issue affects different types of users.

For example, here we’re looking at a website where text might be hard to read. If we choose to simulate dyslexia you can see what the sentences might look like:

You could then interpret subjectively whether the text looks like it would be hard to understand.

There are ways that you can (and should) blend automated and manual testing together. We’re constantly working on that but, for the most part, you should look at a mixture of the two approaches.